By Joe Keast

Although in the 21st century differences between different Christian denominations are mostly no longer a source of antagonism, these differences had a significant impact on the young town of Peterborough toward the end of the 19th century.

One systemic example of this antagonism was the provision of health care. In the mid-1880’s the widow of a wealthy Peterborough businessman, Mrs. Charlotte Nichols, set aside $100,00 for the establishment a hospital in the young, growing town. This important addition to the community was to be managed by a specifically chosen group of business and professional leaders – representatives of the various Protestant denominations, along with the mayor (unless he were not a Protestant). The Nichols Hospital’s services were specifically and exclusively “for the benefit the Protestant population.”

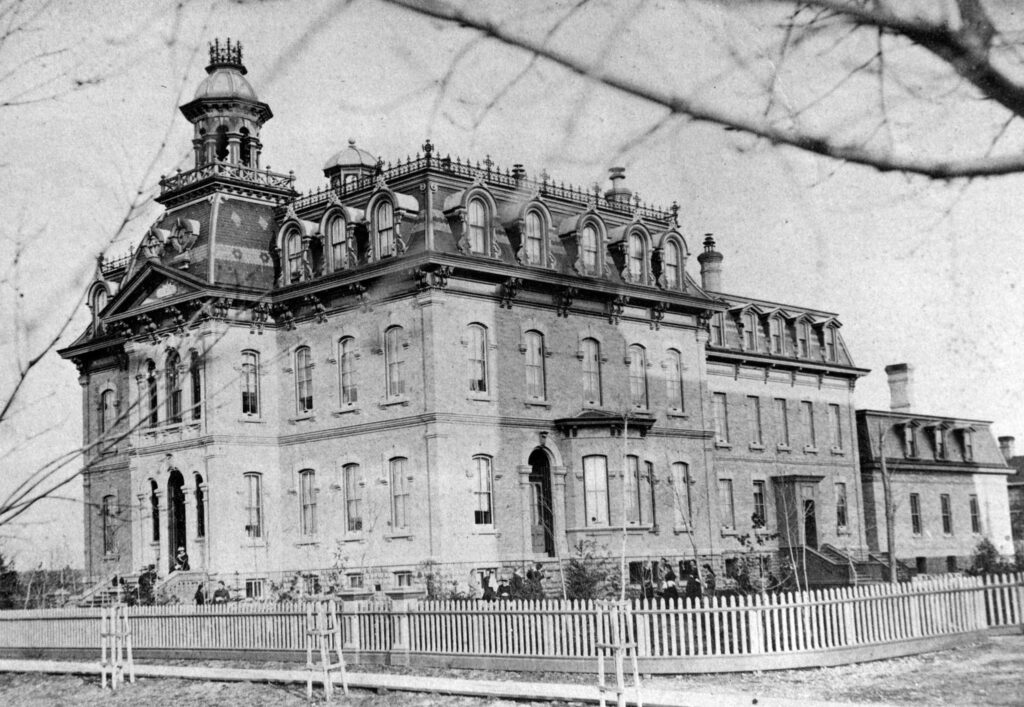

As word of this development reached the attention of Bishop Joseph Thomas Dowling of the Diocese of Peterborough, he began making plans for a hospital whose vision would be more catholic. Bishop Dowling purchased a site across the river in Ashburnham Village – referred as St. Leonard’s Grove and hired local architect John Belcher to design the building. In 1889 Bishop Dowling was transferred to the Hamilton diocese and was succeeded by Bishop Richard Alphonsus O’Connor. With work on the hospital building proceeding, Bishop O’Connor approached the leaders of the Toronto Sisters of St. Joseph, who in previous years had established several hospitals in southern Ontario and Port Arthur and who had convents dedicated to Catholic education in the Peterborough diocese. He asked the Sisters to agree, not only to staff the new hospital, but to allow the formation of a new Congregation for the Peterborough diocese comprising of the Toronto Sisters’ establishments in Cobourg, Port Arthur, and Fort William as well as staff for the Peterborough hospital and a school in Lindsay to be assumed from the Loretto Sisters to serve as a motherhouse for the new Congregation.

With some trepidation, the Toronto Congregation generously agreed to this request. In August of 1890 the construction of the new hospital neared completion. Under the direction of Mother M. de Pazzi, General Superior of the Toronto Congregation, those Sisters who could, gathered in the empty building to hold retreat and the election of the first leadership group. The retreat ended on August 15th with the election of Mother Austin Doran as the General Superior of the new congregation. A few days later, on August 20, Bishop O’Connor presided over the dedication and official opening of the hospital. He proclaimed that “its doors will be open to the sick of all denominations, to Jew and Gentile, Catholic and Protestant.”

Mayor Stevenson was moved by this universal decree and agreed that the town would co-operate in retiring the remaining debt. The first Sisters to staff the new hospital were Mother Anselm (O’Connor), Sister Baptista (Keane), Sister Geraldine (Chidwick), and Sister Hilary (Irwin). The next year the Sisters expanded their ministry at the hospital by welcoming 40 people in need of care – the aged, blind, destitute, and orphans. This group had been cared for by the Toronto Sisters, but it was felt that they would be better cared for in their hometown. Eventually this led to the establishment of the House of Providence to care for the elderly and destitute on the hospital grounds, and St. Vincent’s Orphanage to care for children in town.

Over the next century, St. Joseph’s Hospital served the citizens of Peterborough City and County with compassionate, professional medical care. During this time the hospital underwent a series of major additions and the level of medical care expanded to keep up with all the changes and improvements in medical care. In the 1990’s, when the cost and complexity of providing medical care became onerous, the provincial government mandated the St. Joseph’s and Civic Hospital (the successor to the Nichols Hospital) be amalgamated to form the Peterborough Regional Health Center.

Thus, an endeavor which came to be because of religious antagonism blossomed, and when the time was right evolved into the modern medical facility that residents of Peterborough enjoy today.