Thanks in part to Library and Archives Canada’s Documentary Heritage Communities Program, the archives has been able to preserve, arrange, and describe the majority of the annals from the Congregations of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Pembroke, Hamilton, and London!

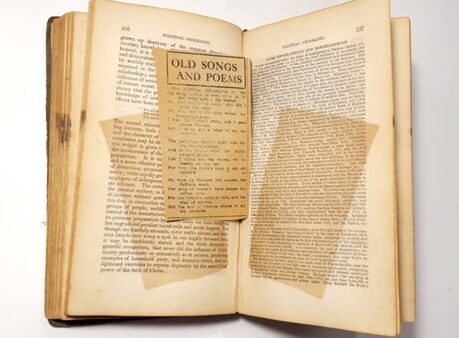

These annals are written logs documenting the day-to-day activities of the Sisters while fulfilling various ministries across Canada and abroad. Many of the annals also include photographs, news clippings, and ephemera from the missions.

The finding aid for the Pembroke annals is available on Archeion, Ontario’s Archival Information Network. Keep an eye on our Archeion page as we work to upload the finding aids for the annals of London and Hamilton.