By Noelle Tangredi

There are many reasons to like old houses–the architecture, the decorative details and high ceilings. but many old home lovers feel a connection to the history of their old home. Every house has its story. Wouldn’t it be great to uncover those stories and learn about the families that lived there before you? It’s not that difficult to do—and believe me, it can become a little addicting!

Things you can often find out about your old home include: the year it was built, the first owners and or tenants, the original purchase price or historical assessments, information about historic land transactions and subdivision plans. You can also piece together stories of families that lived there and what their lives were like, if any of them went to war, what kind of jobs they may have had, when they were born, married and died and more. Nothing is a sure thing and sometimes information is limited, difficult to find or interpret, but once you find something, it’s hard not to keep going. Below are some tips on how and where to start.

Start with determining the build date

Check with your local architectural preservation society about your house first and see if there’s any information written on it already. If it’s a designated heritage home, there may be a report written on it. If you are interested in the architecture of your home, a good primer on architecture styles in Ontario can be found at this link: Index Page – Ontario Architecture.

The age of your house can be determined pretty closely by using several different resources:

Researching the building

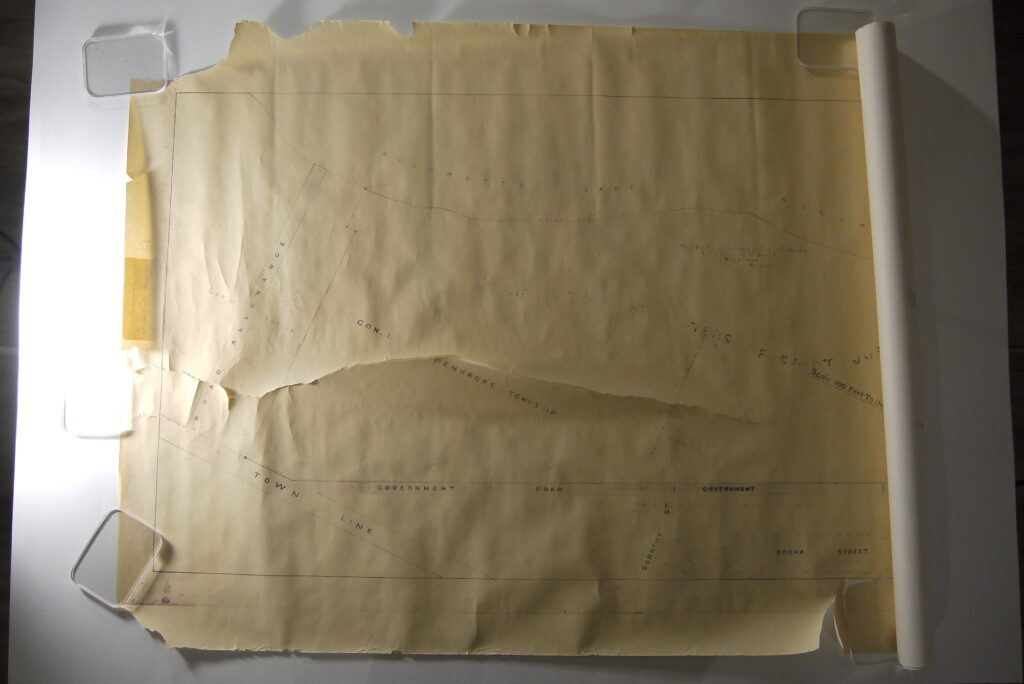

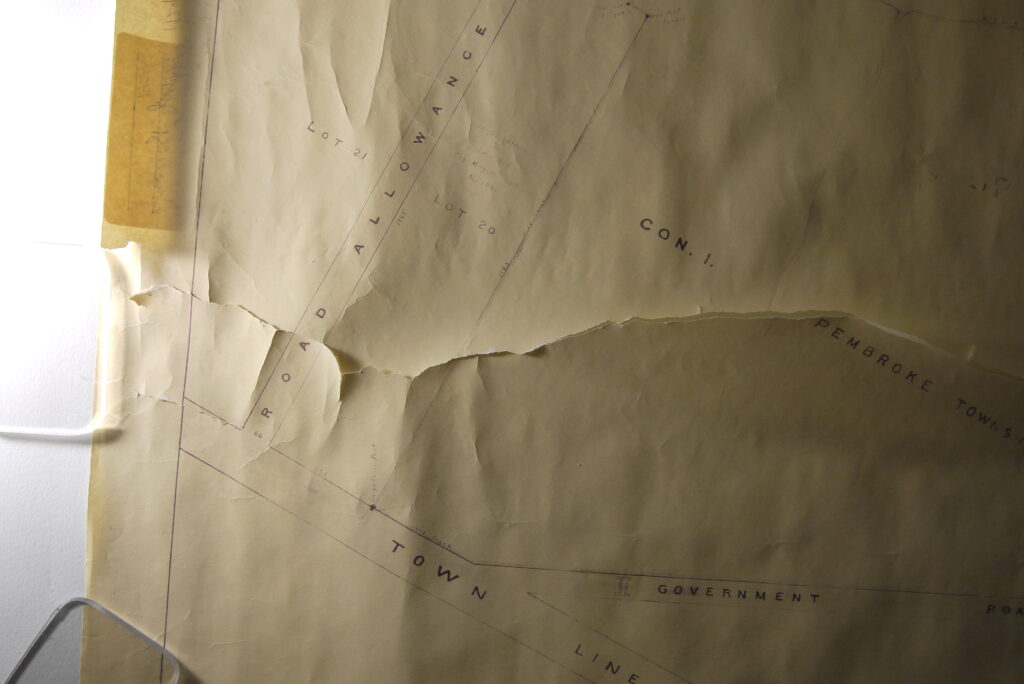

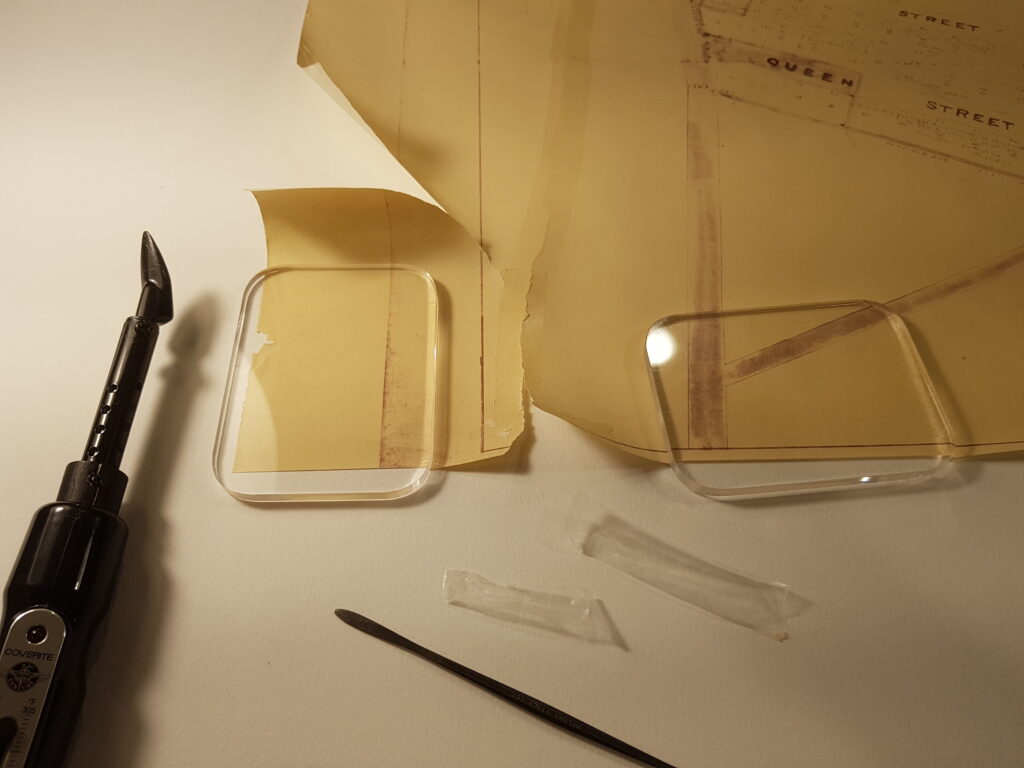

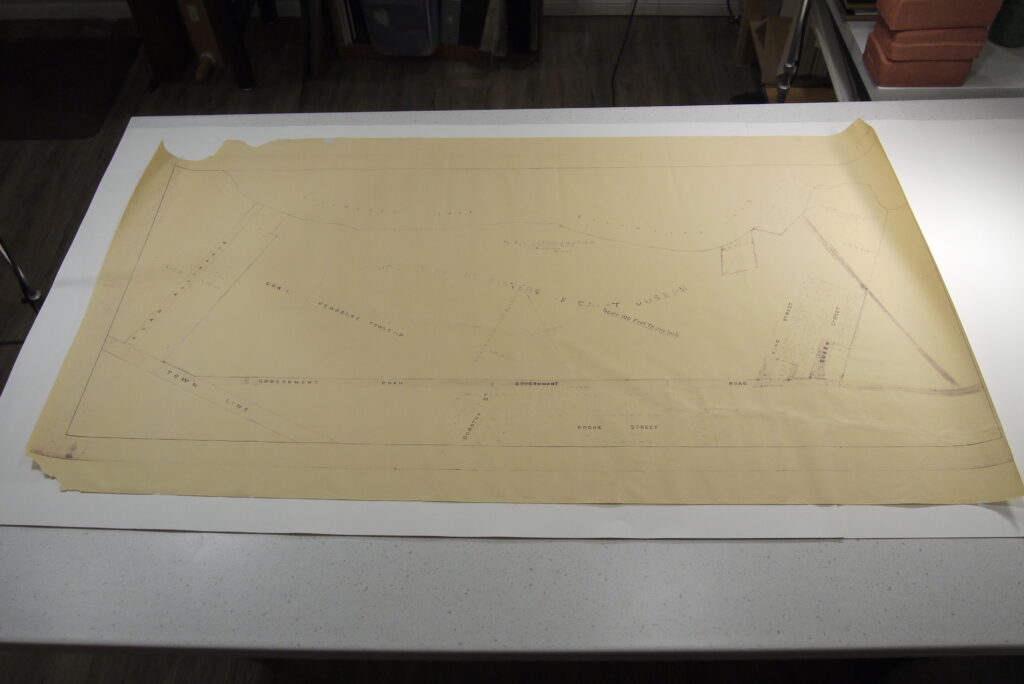

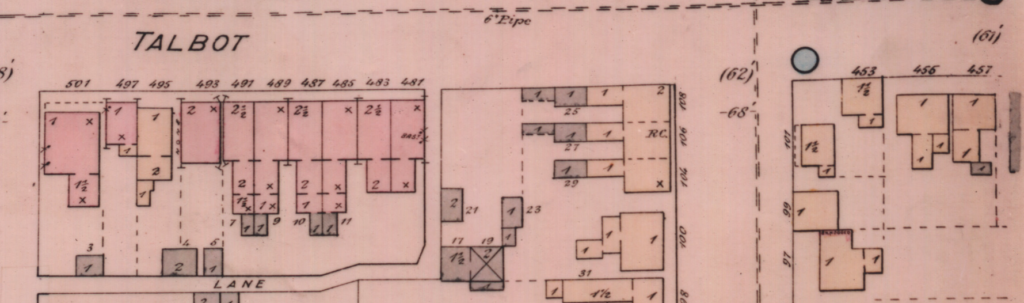

Fire Insurance Plans

These are hand drawn maps that show what buildings were on a particular lot according to the date it was last revised. It provides a visual footprint of the building, what materials it was made from and if there are any outbuildings. These very helpful to pinpoint a timeframe for your house’s construction and even if there might have been another house on the lot that was replaced by the current one. The map provides clues to changes in the structure or house number or even street name changes over the years. These maps are often kept in City or County Archives or Libraries and are sometimes available online.

City Directories

All cities had a directory that functioned as a phone book before there were telephones (and even afterwards). They have two sections. One is organized by street address (street names in alphabetical order, separated by odd and even numbers with cross streets shown). This section will show the name of the head of the household at each address. If you have an idea of when your house might have been built, start with that. If you find it, keep working backwards until you do. This will be the year it was finished and occupied. The previous year will likely be a more accurate build date based on when the information was gathered for the directory and when it was published. If you don’t find your address, keep going ahead until you do. Sometimes you’ll find it listed as “unfinished house” or “new”.

The second part of the directory is alphabetical by last name. Use this to find out the occupation of the head of the household and sometimes others living at the same residence (a wife’s name, for example). If the directory names the householder’s place of business, you can also consult the directory for more information on what kind of work was done there, the address and even sometimes an advertisement.

Directories are usually the easiest way to pin down information on your home’s history. These are usually located either in their original format or on microfiche in your local library or city and county archives. Some are even located online.

Tax assessment rolls, Registered Plans and Property Transactions

Although a little more complicated to get a hold of and understand, these documents can give you very interesting information about who built your house, when and for how much. What the land was assessed at for tax purposes over the years and even strange details like how many dogs, chickens or horses were on the property when it was assessed! It can also answer questions about whether the first occupants of the house were owners or tenants. These records could be located in your local city or county archives or possibly through your city hall.

Researching Occupants’ Lives

Canadian Censuses

Once you know the year of construction and the names of early occupants and possible occupations, you can start pulling out the stories of their lives. A good place to start is the censuses for your area. Library and Archives Canada has a searchable database here: Censuses – Library and Archives Canada. If you don’t come up with your people right away, try various family members and different years. Sometimes transcription or spelling errors happen in digitization. The census will reveal all of the people living in the house when the census taker visited the home. This is a good way to find out children’s names and the birthdates of family members to help with further research. You may also discover that others lived in the home, such as lodgers, other relatives or servants. Ancestry.ca also has census records and if you can’t find your people on the LAC site, you might have luck there.

Ancestry.ca

Armed with what you learned from the census will help you more accurately search in genealogy services such as: Ancestry.ca. Here you can find out birth, death and marriage dates and sometimes school info, photos and family trees. These details will help pull together various bits of information into stories, such as the lives of new immigrants, the birth of family businesses and the tragedies of early deaths due to local epidemics, war or accidents. Ancestry.ca is usually available for free through your local library.

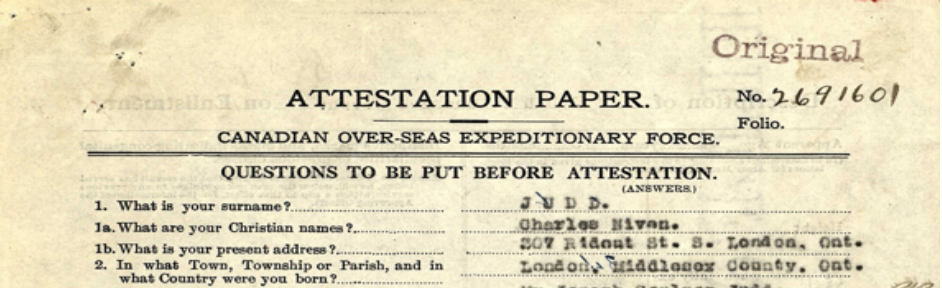

Military Records

If you suspect that an occupant of your house may have served during wartime, you can search for and read personnel files on the Library and Archives Canada website. Ancestry.ca may have some documents but the LAC website has the complete files:

Library and Archives Canada.

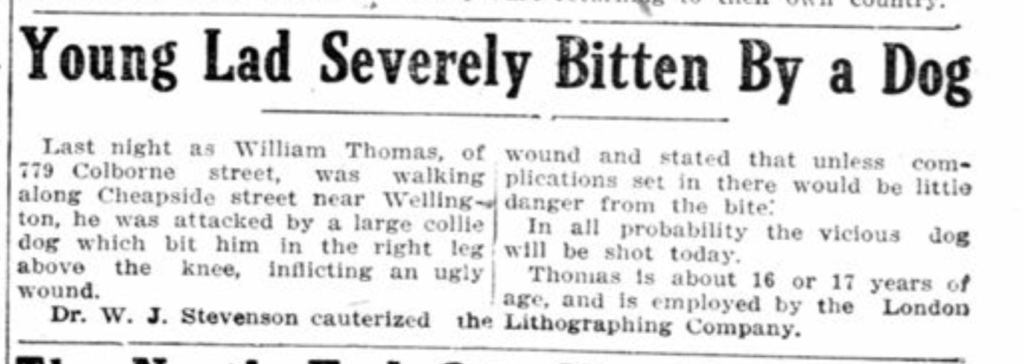

Local Newspaper Articles

Your local library or archives may have local newspaper articles available but likely not searchable. The website Canadiana.ca houses many digital documents and has a section with local magazines and newspapers. I’ve found that newspaper articles from “back in the day” usually include a lot of personal information, including home addresses. If you search these papers for you address, you may find some pretty interesting stories! Visit: Serials: Periodicals, Annuals and Newspapers – Canadiana.

These are just a few places for you to start. Local librarians, archivists and historians will be able to point you in the direction of more information. Happy researching!