Preserving and caring for records of enduring value means that the legacy of a person or community is kept for future generations. This is the mission of our archives. We hope this short video captures this.

Outreach

Resources for Religious Archivists

Did you know that the Society of American Archivists has a special section to advocate for and support religious archivists? It is the Archivists of Religious Collections Section and they provide valuable training support and resources to religious archivists.

One way they do this is by sharing resources such as forms and manuals and policies on their microsite. The resources are free to download and adapt and are available here: Models and Resources.

Another ways is through organizing and delivering Lunch and Learn webinars which are training sessions with amazing presenters! You can view recordings of these webinars on the YouTube channel: SAA ARCS Resources YouTube channel.

Besides the webinars, the Archivists of Religious Collections Section also holds Archival Chats which are open discussions around a topic, giving archivists the chance to network and share ideas.

Our archives is proud to support the work of the Society of American Archivists – Archivists of Religious Collections Section. The Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada generously hosts the Lunch and Learn and Archival Chat sessions that are open to all archivists, and provide invaluable support to religious archivists in particular.

Archiving websites

We were very pleased to be accepted into the Internet Archives web archiving program, the Community Webs Program, this year. These days, so many organizations have websites, and these are sources of rich information about their organization, activities, and history. They are sources of multimedia including photographs, videos, and audio recordings. Websites are records just like physical materials, but they are different because they undergo constant change, and are subject to degradation and loss. In fact, according to Jill Lepore in her article in the New Yorker, “The Cobweb,” she states the lifespan of a webpage can be as little as 100 days! (see “The Cobweb,”)

So how do we preserve these fragile and ephemeral records? Thankfully, the vision of Brewster Kahle who founded the Internet Archive, has provided us with a tool, Archive-It, which can capture websites and replay them in their full functionality with another tool, the Wayback Machine.

As they explain it, the Community Webs Program provides participants with the opportunity to capture the stories of communities and diversify the historical record by preserving many voices. It provides the tools and skills to preserve the websites and social media platforms of local communities and their citizenry, attesting to their presence, visions, dreams, and hopes, so that future generations will know…we were here at this moment in time.

According to the Community Webs Program, there are now more than 150 members of this program. “These organizations have collectively archived over 100 terabytes of web-based community heritage materials, including more than 800 collections documenting the lives of local citizens, marginalized voices, and groups often absent from the historic record. The program and its participants have also created open educational resources relating to web archiving, digital preservation, community archiving, and collection development, explored new forms of local engagement and partnerships through public programming and crowdsourcing, and had their digital collections used by scholars and in computational research work.” (see About Community Webs)

We feel very fortunate to have been selected to participate in the Community Webs Program, and have been working to archive our own congregational website, and related websites of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada and the United States. It has been a learning curve, but we are so very grateful to the wonderful staff at Internet Archive who are so supportive, patient, and willing to guide us in this journey. While still a work in progress, you can see what we have accomplished so far by visiting our Community Webs site: Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada

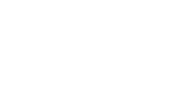

Caring for your Family Bible

By Jennifer Robertson, Book and Paper Conservation Services

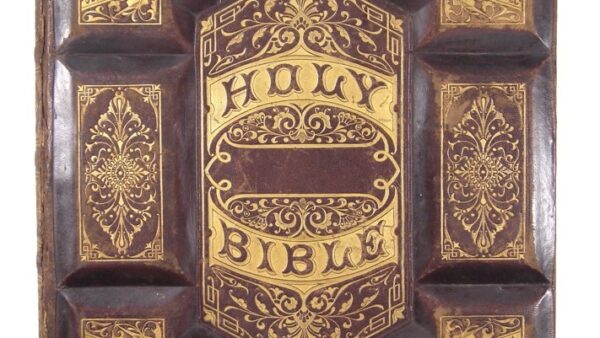

If you are lucky enough to have a family Bible that belonged to your ancestors, you probably treasure it very much. Family Bibles are often kept and passed down through generations, perhaps with precious memories attached of reading passages together, a special place in your relatives’ home, or even with written records inside. They can be important sources of genealogical information if a family tree was kept, as many 19th century Bibles included specially printed pages for recording births, marriages and deaths in the family. Whatever the significance they carry, it is important to keep the physical book safe from damage and deterioration, so that it can continue to be passed down to later generations.

There are three factors that should be considered when caring for your family Bible; Environment, Storage, and Handling. All have an impact on the condition of your Bible, and you can make adjustments in many ways to keep it in good condition.

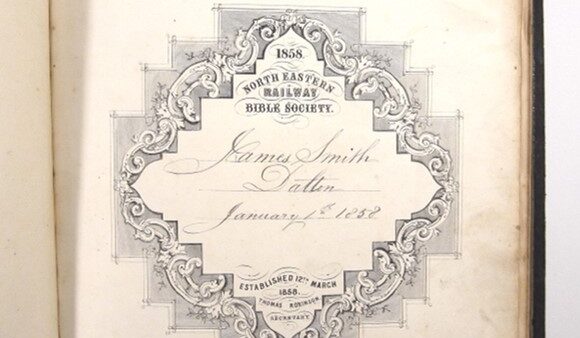

Environment

A Bible, like any book or artifact, is affected by the environmental conditions in which it lives. This includes factors like temperature, relative humidity (RH) and light. High temperatures and humidity can cause damage to the paper, cloth or leather used to make the Bible. The higher the temperature, the more dry and brittle the paper and leather will become, and the more likely it is to crack. High humidity, and the change between high and low humidity that is natural as weather swings from summer to winter, causes expansion and contraction of materials, putting strain on weak areas like covers, spine and endpapers. This also makes them more likely to crack, break or peel. Light can damage materials with sensitive dyes or colourings, resulting in faded and discoloured leather, cloth or illustrations.

The ideal environment for a Bible is between 18-21°C and 45-55% RH. Too high a temperature and too low RH results in brittleness and cracking, but too high can cause the growth of mould. These mid-levels are just the right amount to keep paper, cloth and leather healthy and supple. To keep your Bible safe, avoid storing it in a damp basement or dry attic, or close to a radiator or hot air vent. If possible, run an air conditioner and dehumidifier in the summer or a humidifier in winter if your home is very dry.

Keep your Bible out of direct light to prevent fading of materials. Direct sunlight falling on a bookshelf or high ambient light in a room with many windows can do damage after only a few months. A darker, interior room is best, or else keep the Bible in a drawer or storage box when not in use.

Storage

Careful storage can help preserve your Bible by keeping it safe from light, dirt and pests. Dust or soot from a fireplace, cigarette smoke or air pollution can soil or discolour your Bible, and frequent cleaning to remove these can also cause damage. If the Bible is kept in a seldom-used drawer or box with other items, it may also be tempting to pests such as silverfish, who like to eat the starch-based materials in paper and glue. A clean, dry, protected storage location goes a long way towards preserving a Bible or any special artifact.

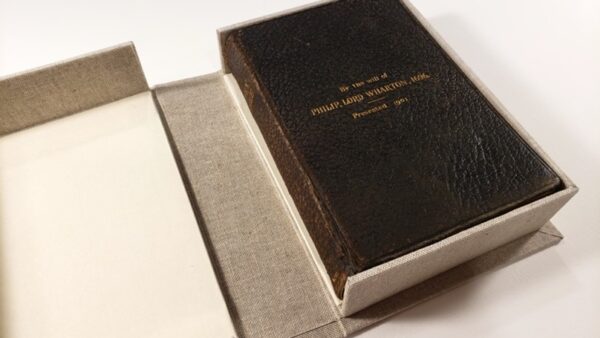

An archival storage box or a clean, dedicated drawer or cupboard can offer safety for a Bible, protecting it from light and dirt, as long as some precautions are taken. If the Bible is large and heavy, it is a good idea to store it laying flat, on the back cover; if it is smaller, it can be stored standing vertically on a shelf, as long as it is supported on either side by other books of a similar size.

If you choose to store it in a drawer or cupboard, make sure the space is clean and dry, and line it with acid-free tissue or mylar to prevent transfer of acidity from wood or cardboard. Make sure there are no other objects close to the Bible that might cause damage when shuffled or jostled around. Wrapping it in acid-free tissue can also help to keep it clean and safe within the storage area.

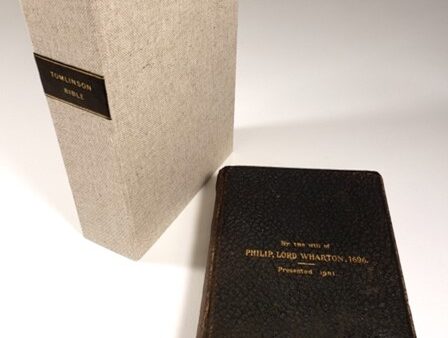

An archival box is an ideal storage solution for a Bible. These come in different sizes, and are available from Library and Archives suppliers like Carr McLean or Brodart in Canada. They are made of special cardboard material that is acid-free and won’t cause damage to books. Again, wrapping it in acid-free or buffered tissue within the box is a good idea, especially if the box is slightly larger than the book. A snug fit is best, so the book won’t slide around if it is being moved. If you want to protect it more elegantly, you can commission a custom clamshell box to fit your book exactly, and have the box decorated and labelled in any way you wish.

Handling and Use

Improper handling and use can cause a lot of damage to a delicate family Bible. Tears and breaks in the paper, detached covers, stains and spots all result from handling without proper precautions.

If you are going to take your Bible out to read or view, first make sure you have a clean, dry space to set it out and open it. Clear a table of other objects, and especially make sure there is no food or drink close by that could spill. Wash your hands with unscented soap and dry them thoroughly. Contrary to popular believe, clean dry hands are much better than white gloves for handling delicate books, as long as you are careful. Wearing gloves can dull your dexterity, and the cloth can catch on delicate pages causing them to break. The light oils on your hands can also help to keep the leather supple on the covers of a Bible.

If you are lifting it out of a box, go slowly and use both hands. If you are taking it off a bookshelf, be careful to grasp the book using your fingers and thumb on front and back covers, with your hand across the spine; never pull the book back with your finger hooked over the top and pulling on the spine, as this is likely to rip the endcap off and damage the binding.

When paging through the book, set it on the table and support the cover as you hold it open, either with one hand or a book cradle or support. This will help keep the book open no further than a 90° angle, and avoid cracking the spine. Try to avoid opening the pages all the way to 180°, or letting the cover bend back even further.

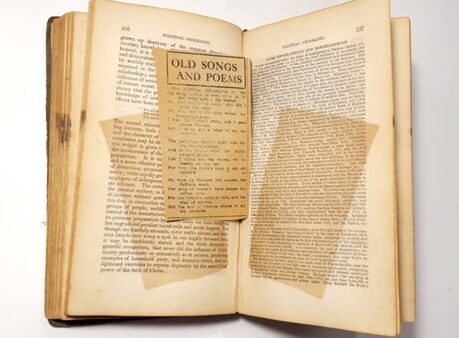

Be sure to use a pencil and acid-free paper to make notes, or to leave a marker in the pages. Never leave a post-it note, newsprint or other scrap of unidentified paper within the Bible, as they can transfer colour or acidity to the pages, causing discolouration. It should also be said, never use paper clips, staples, rubber bands or other objects to mark a page!

If you want to consult a specific page frequently, say to show the genealogical entries to family or friends, you might consider taking a high quality photograph and printing out the image, so that you can pass around a facsimile rather than putting strain on the original material. The more frequently the book is opened the more likely the binding will suffer irreversible damage, and if you are simply referencing the information you don’t need to view the original page. However, avoid the use of a flat-bed scanner to reproduce a page in the Bible, as manipulating the book to lie open on a scanner bed is a risk to the binding. A digital photograph printed out is just as good, and can sometimes be enhanced to show text more legibly than the original.

In the past, collectors recommended applying oil-based leather dressing to bookbindings to keep the leather supple and soft; however, book conservators now advise against this, as excessive or inappropriate treatment can easily cause the opposite effect on leather. Keeping books clean and dry and away from extremes of humidity and temperature is a much safer way to preserve their bindings. If you have questions about repairs or rebinding options for your Bible, consult a professional conservator, bookbinder or archivist for more detailed information.

Following these guidelines will help preserve your family Bible for many years to come!

Resources

Resources:

Book and Paper Conservation Services – Conservation and repair, clamshell boxes etc.

Canadian Conservation Institute: Basic Care of Books

Library of Congress: Care, Handling, and Storage of Books

Brodart – Supplier of Library and Archives materials, such as archival storage boxes, acid-free tissue, book supports, etc.

Carr McLean – Supplier of Library and Archives materials, such as archival storage boxes, acid-free tissue, book supports, etc.

Researching your heritage home in Ontario

By Noelle Tangredi

There are many reasons to like old houses–the architecture, the decorative details and high ceilings. but many old home lovers feel a connection to the history of their old home. Every house has its story. Wouldn’t it be great to uncover those stories and learn about the families that lived there before you? It’s not that difficult to do—and believe me, it can become a little addicting!

Things you can often find out about your old home include: the year it was built, the first owners and or tenants, the original purchase price or historical assessments, information about historic land transactions and subdivision plans. You can also piece together stories of families that lived there and what their lives were like, if any of them went to war, what kind of jobs they may have had, when they were born, married and died and more. Nothing is a sure thing and sometimes information is limited, difficult to find or interpret, but once you find something, it’s hard not to keep going. Below are some tips on how and where to start.

Start with determining the build date

Check with your local architectural preservation society about your house first and see if there’s any information written on it already. If it’s a designated heritage home, there may be a report written on it. If you are interested in the architecture of your home, a good primer on architecture styles in Ontario can be found at this link: Index Page – Ontario Architecture.

The age of your house can be determined pretty closely by using several different resources:

Researching the building

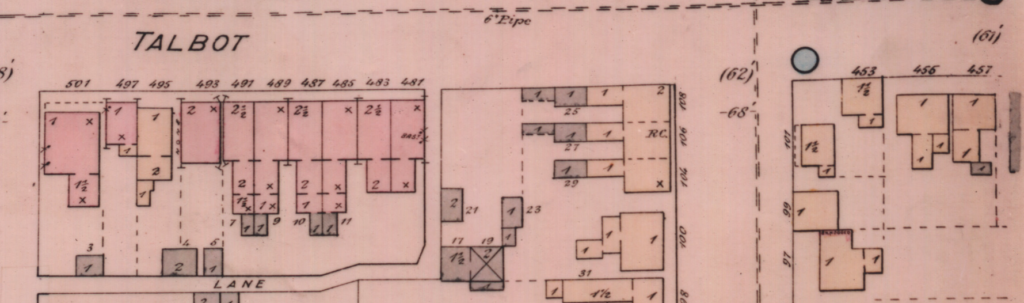

Fire Insurance Plans

These are hand drawn maps that show what buildings were on a particular lot according to the date it was last revised. It provides a visual footprint of the building, what materials it was made from and if there are any outbuildings. These very helpful to pinpoint a timeframe for your house’s construction and even if there might have been another house on the lot that was replaced by the current one. The map provides clues to changes in the structure or house number or even street name changes over the years. These maps are often kept in City or County Archives or Libraries and are sometimes available online.

City Directories

All cities had a directory that functioned as a phone book before there were telephones (and even afterwards). They have two sections. One is organized by street address (street names in alphabetical order, separated by odd and even numbers with cross streets shown). This section will show the name of the head of the household at each address. If you have an idea of when your house might have been built, start with that. If you find it, keep working backwards until you do. This will be the year it was finished and occupied. The previous year will likely be a more accurate build date based on when the information was gathered for the directory and when it was published. If you don’t find your address, keep going ahead until you do. Sometimes you’ll find it listed as “unfinished house” or “new”.

The second part of the directory is alphabetical by last name. Use this to find out the occupation of the head of the household and sometimes others living at the same residence (a wife’s name, for example). If the directory names the householder’s place of business, you can also consult the directory for more information on what kind of work was done there, the address and even sometimes an advertisement.

Directories are usually the easiest way to pin down information on your home’s history. These are usually located either in their original format or on microfiche in your local library or city and county archives. Some are even located online.

Tax assessment rolls, Registered Plans and Property Transactions

Although a little more complicated to get a hold of and understand, these documents can give you very interesting information about who built your house, when and for how much. What the land was assessed at for tax purposes over the years and even strange details like how many dogs, chickens or horses were on the property when it was assessed! It can also answer questions about whether the first occupants of the house were owners or tenants. These records could be located in your local city or county archives or possibly through your city hall.

Researching Occupants’ Lives

Canadian Censuses

Once you know the year of construction and the names of early occupants and possible occupations, you can start pulling out the stories of their lives. A good place to start is the censuses for your area. Library and Archives Canada has a searchable database here: Censuses – Library and Archives Canada. If you don’t come up with your people right away, try various family members and different years. Sometimes transcription or spelling errors happen in digitization. The census will reveal all of the people living in the house when the census taker visited the home. This is a good way to find out children’s names and the birthdates of family members to help with further research. You may also discover that others lived in the home, such as lodgers, other relatives or servants. Ancestry.ca also has census records and if you can’t find your people on the LAC site, you might have luck there.

Ancestry.ca

Armed with what you learned from the census will help you more accurately search in genealogy services such as: Ancestry.ca. Here you can find out birth, death and marriage dates and sometimes school info, photos and family trees. These details will help pull together various bits of information into stories, such as the lives of new immigrants, the birth of family businesses and the tragedies of early deaths due to local epidemics, war or accidents. Ancestry.ca is usually available for free through your local library.

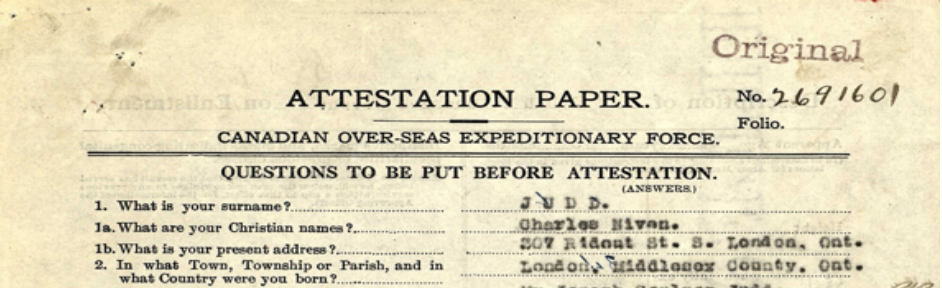

Military Records

If you suspect that an occupant of your house may have served during wartime, you can search for and read personnel files on the Library and Archives Canada website. Ancestry.ca may have some documents but the LAC website has the complete files:

Library and Archives Canada.

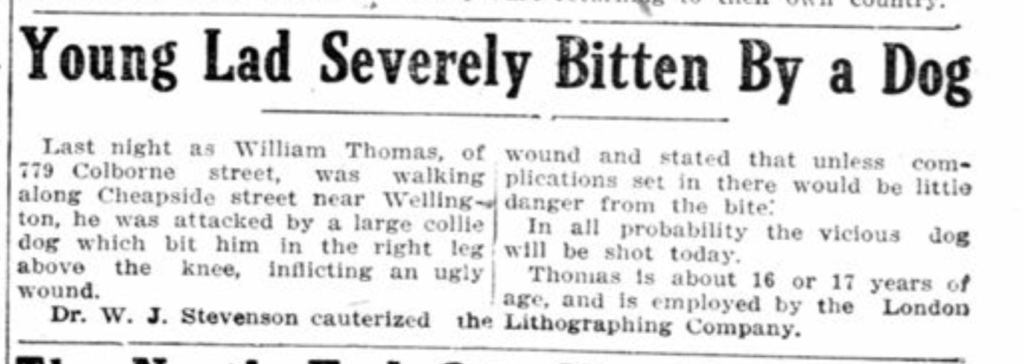

Local Newspaper Articles

Your local library or archives may have local newspaper articles available but likely not searchable. The website Canadiana.ca houses many digital documents and has a section with local magazines and newspapers. I’ve found that newspaper articles from “back in the day” usually include a lot of personal information, including home addresses. If you search these papers for you address, you may find some pretty interesting stories! Visit: Serials: Periodicals, Annuals and Newspapers – Canadiana.

These are just a few places for you to start. Local librarians, archivists and historians will be able to point you in the direction of more information. Happy researching!